New York, here we come! We’re on our way today, taking the Bitterns in Rice Project to the Global Food Security Conference. We’re chuffed to be part of the impressive program and look forward to sharing what we learn from the conference and in the rice fields of California that we’ll tour afterwards.

Below is the submitted summary of our presentation for the water use and natural resources theme on Tuesday:

Co-management of water for rice production and wetland biodiversity in Australia

M.W. Herring1, N. Bull2, M. Robb3, W. Robinson4, A. Silcocks5

1 Murray Wildlife, Australia; 2Ricegrowers’ Association of Australia; 3Coleambally Irrigation, 4Charles Sturt University; 5Birdlife Australia.

Increasing global demand for food is resulting in new agricultural areas and more intensive production in existing ones. Without considered, integrated management, these trends will exacerbate biodiversity decline. Large conservation areas like nature reserves are central yet inadequate in conserving biodiversity, and there is growing recognition of the potential conservation role of novel, anthropogenic habitats. The biodiversity values of Australian rice crops are poorly known, despite their potential conservation role as agricultural wetlands in the Murray-Darling Basin. Our aim was to estimate the population size and determine the extent of breeding for waterbird and frog species using Australian rice fields, especially the globally endangered Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus), a cryptic wetland bird. We also aimed to determine if bitterns or other species were associated with certain agronomic characteristics of rice fields in order to begin informing guidelines for both sustainable intensification and wildlife-friendly farming (‘land-sharing’) in these systems.

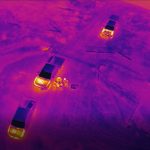

In addition to opportunistic surveys and the verification of landholder records, for three rice-growing seasons from 2012-2015, we randomly selected rice farms to establish representative study sites. During the most recent season (2014-2015), this approach incorporated 80 sites of 23-30 ha, covering 41 different farms in two of the three main rice-growing regions: Murrumbidgee and Coleambally Irrigation Areas. This 2050 ha sample comprised 6.1% of the total rice crop in those areas (33 500 ha). Waterbirds and frogs were sampled twice at each site using a 1-hour survey conducted within three hours of dawn and dusk. A range of habitat and agronomic variables, such as water depth and sowing method, were recorded. Bittern nest searches were conducted where they had been recorded, while breeding observations for all species were noted.

Rice fields supported 53 waterbird and seven frog species. The populations of several waterbird species, such as Whiskered Tern and Golden-headed Cisticola, were significant, with estimates of more than 10 000 birds. Populations of at least three frog species, particularly the Spotted Marsh Frog, extend well into the millions, possibly exceeding a billion. Several threatened species were also found in relatively significant numbers, notably the Southern Bell Frog and Australian Painted Snipe, while there were six species of migratory shorebird recorded.

Dependent on assumptions, our most recent habitat occupancy modelling for the Australasian Bittern indicates a population of approximately 440 mature individuals in the Murrumbidgee and Coleambally parts of the rice-growing region. There are substantial detectability issues, highlighting this figure as a minimum. The Murray Valley typically comprises 40-50% of the rice area and has not yet been sampled randomly, but we assume a population density considerably lower than the Murrumbidgee and Coleambally regions, and therefore estimate the Australasian Bittern population using rice fields at 500-1000 mature individuals.

A total of 15 waterbird and three frog species were recorded breeding in rice crops. A total of 14 Australasian Bittern nests were found, primarily from randomly selected rice farms, indicating the widespread nature of their breeding in rice. Fledged young have been recorded for bitterns and several other species, indicating successful breeding.

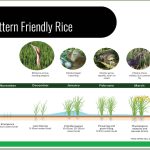

Australasian Bitterns arrive in rice crops in November and December, when the rice height is around 30-40 cm. Bitterns showed a strong preference for aerially-sown crops, avoiding direct-drill/combine-sown crops, presumably because of the associated delayed permanent water and dry phases, affecting the prey base. They were often recorded roosting and feeding in stands of Typha spp. and associated with the relatively open rice field edges.

The value of Australian rice fields to biodiversity has been overlooked. These results for waterbirds and frogs represent significant populations for a range of species, highlighted by the documentation of the largest known Australasian Bittern breeding population, representing between approximately one quarter and one third of the global total of 1500-4000 mature individuals (Figure 1).

The results have been used to develop bittern-friendly rice growing guidelines. They have been widely distributed and incorporated by some rice growers through their goodwill. However, much more needs to be done to maintain and enhance the biodiversity conservation values of Australian rice fields.

The shift towards direct-drill/combine-sown crops, for water savings and to avoid damage by ducks early in the season, is likely to impact the Australasian Bittern population negatively. In order to make this intensification sustainable for the bittern population, water could be co-managed. To ensure crops have early permanent water, the delivery of environmental water or the subsidy of additional water costs to the landholder, could be used to offset these impacts. Another option is for bittern-friendly rice to be sold at a premium, accounting for additional costs. Dedicated habitat bays as part of the rice field or adjacent constructed wetlands, also using environmental water or subsidies, could be used to enhance biodiversity values.

Figure 1: Australian rice fields support the largest known breeding population of the globally endangered Australasian Bittern.